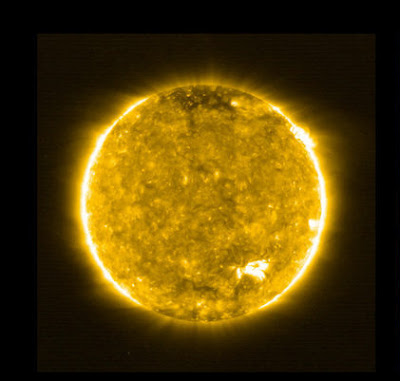

“When the first images came in, my first thought was this is not possible, it can’t be that good,” David Berghmans, principal investigator for the orbiter’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager instrument, told a press briefing on 16 July. “It was much better than we dared to hope for.”

“The Sun might look quiet at the first glance, but when we look in detail, we can see those miniature flares everywhere we look,” said Berghams, a solar physicist at the Royal Observatory of Belgium, in a statement.

The fires are millions or billions of times smaller than solar flares that can be seen from Earth, which are energetic eruptions thought to be caused by interactions within the Sun’s magnetic fields. The mission team has yet to figure out whether the two phenomena are driven by the same process, but they speculate that the combined effect of the many campfires could contribute to the searing heat of the Sun’s outer atmosphere, known as the corona. Why the corona is hundreds of times hotter than its surface is a longstanding mystery.

The images, taken by the ultraviolet imager on 30 May and released on 16 July, were captured 77 million kilometres from the Sun’s surface (Earth is about 150 million kilometres from the Sun). A daring NASA mission called the Parker Solar Probe has flown even closer and will get within just 6.2 million kilometres during its mission—inside the corona itself—but the environment is so harsh that it does not carry a camera facing the Sun. Meanwhile from Earth, the Daniel K. Inoye Solar Telescope, in Hawaii, has taken higher resolution images of the Sun than the orbiter, but these do not fully capture the star’s light, because Earth’s atmosphere filters out some ultraviolet and X-ray wavelengths.

Scientists are excited about the potential of the Solar Orbiter, an international collaboration that launched in February and carries 10 instruments to image the Sun and study its environment. The spacecraft will eventually switch its orbit to study the Sun’s polar regions for the first time. “We’ve never been closer to the Sun with a camera, and this is just the beginning of a long epic journey with Solar Orbiter, which will take us even closer to the sun in two years’ time,” said Daniel Müller, the mission’s project scientist, at the briefing.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on Nov, 2022.

.jpg)

0 Comments